Earth Restored

Earth Restored

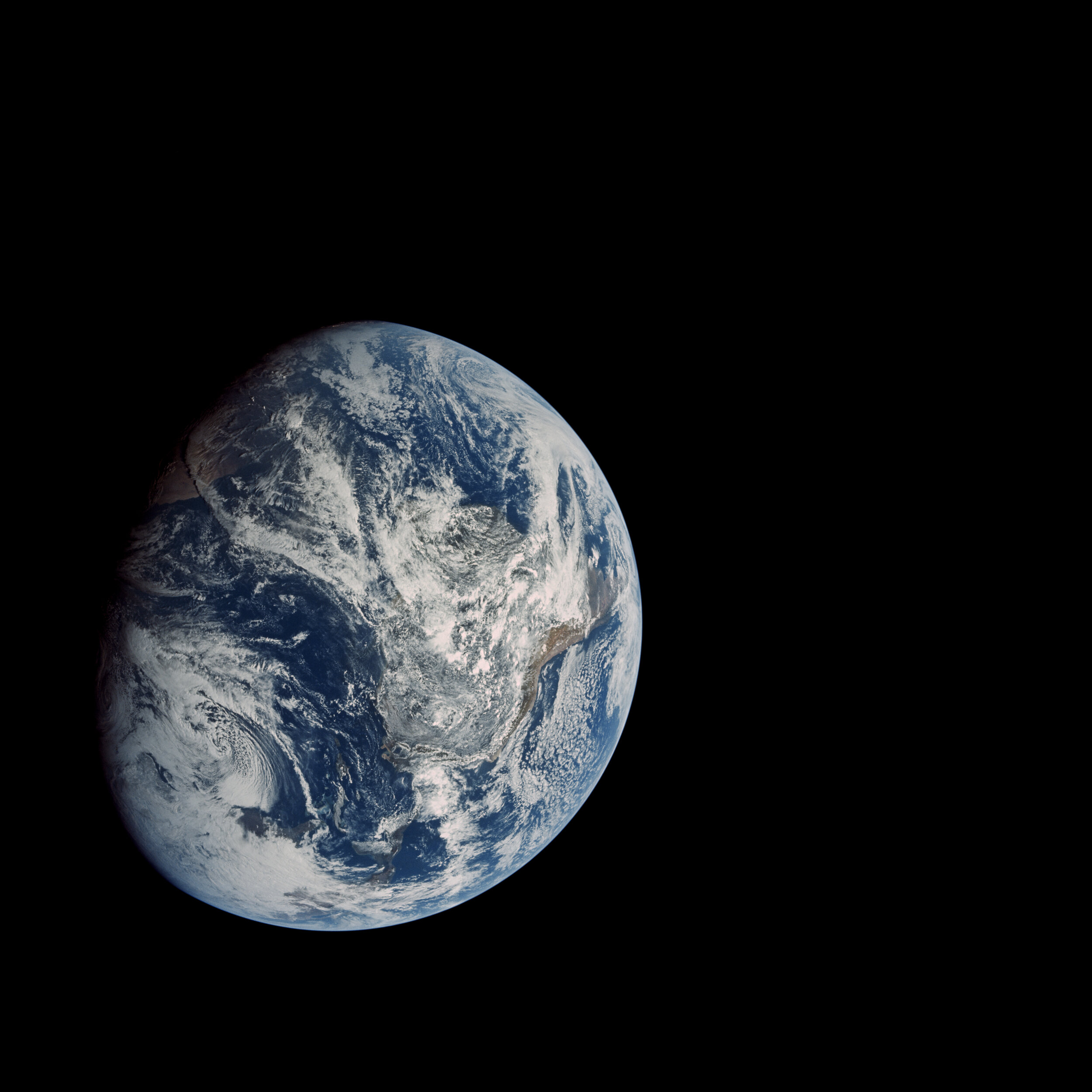

Only 24 people have journeyed far enough to see the whole Earth against the black of space.

The images they brought back changed our world.

Here is a selection of the most beautiful photographs of Earth

— iconic images and unknown gems —

digitally restored to their full glory.

Turn your device sidewise during the slideshow to see the story behind each image, and the link to the full resolution version.

In search of the perfect shot

I was struck by the beauty of Saturn.

The Cassini spacecraft had spent years in increasingly daring orbits, capturing thousands of images of that enigmatic world, before plunging deep into Saturn itself. The photographs were breathtaking, revealing a silent majesty.

Exhilarated, I turned to the Earth. Cassini was the first spacecraft to enter Saturn’s orbit, but Earth has had thousands. The photographs would be exquisite. I couldn’t wait.

But try as I might, I couldn’t find anything to compare.

It wasn’t that Earth itself was any less beautiful, but that there were no photographs which did justice to that beauty. How could this be?

Most recent Earth photography is from the International Space Station. It is a superb vantage point, with excellent equipment and skilled photographers. But its position in low Earth orbit is just too close to allow photographs of the entire planet. If the Earth were a schoolroom globe, 30 centimetres across, the ISS would be viewing the Earth from less than a centimetre away — far enough to see a curving horizon and the black of space, but not to see the whole Earth. In fact, being so close, it can see just 3% of the Earth’s surface at a time.

To take a portrait of our planet you need to step further back. For example, to geostationary orbit (about 90 times further away) or the Moon (about a thousand times further). From these distances, you can see nearly an entire half of the Earth’s surface at any one time, while remaining close enough for a sharp image.

Some recent spacecraft, en route to distant parts of the solar system, turned their cameras back towards Earth as they departed. In some cases, they were perfectly positioned for the shot. But they never had the right cameras. Their cameras were designed for their scientific missions, not for the opportunistic photograph. Heroic measures can be taken, such as treating their infrared channel as red and ultraviolet as blue, but lead to very unnatural, sometimes garish, renderings of our planet.

Finally, there are the composite images. These recent views of the Earth are computer-generated images, stitched together from many photographs taken from orbits that are too close to provide a synoptic view. These synthetic images are more like illustrations of the Earth for an atlas than photographs, often with unnatural colours or perspectives.

Only APOLLO

To find truly great photographs of the Earth — portraits of our planet — we have to go back to the 1960s and 70s. The Apollo program, with its nine journeys to the Moon, is the only time humans have ever been beyond low Earth orbit; the only opportunity they have had to take photographs of the whole Earth. They did not waste it. With great foresight, NASA equipped the astronauts with some of the best cameras ever made — specially modified Hasselblads, with Zeiss lenses, and 70mm Kodak Ektachrome film. But with the custom modifications, these were not easy to use. The cameras had no viewfinders or range finders, just a simple sighting ring. Composition, focus, and exposure came down to a mix of intuition and guesswork.

Camera — heavily modified Hasselblad 500 EL

Lens — Zeiss Planar 𝑓-2.8/80mm, Zeiss Sonnar 𝑓-5.6/250mm

Film — 70mm Kodak Ektachrome (Colour), and Panatomic-X (BW)

The photographs they took changed the course of history. Iconic images, such as ‘Earthrise’ and ‘The Blue Marble’ showed us our fragile planet, kindling the nascent spirit of environmentalism. And the outside perspective, looking down on all humanity, accentuated our unity, making our Cold War divisions seem petty and small.

These two photographs are among the most famous and widely distributed in history. Yet when I sought beautiful high resolution versions I was disappointed. Each available image was marred by low resolution, bad image compression, blown out highlights, or washed out colours. These were the defining photographs of our time, the best representations of our fragile Earth — but they were neglected; mistreated.

So I went deeper, seeking out the originals. The photographic film from the Apollo missions has been extremely well preserved — stored for posterity in a freezer within NASA’s archives. The original film (and several analog duplicates) have been digitally scanned several times over the years. And to my delight many of the raw scans were accessible online.

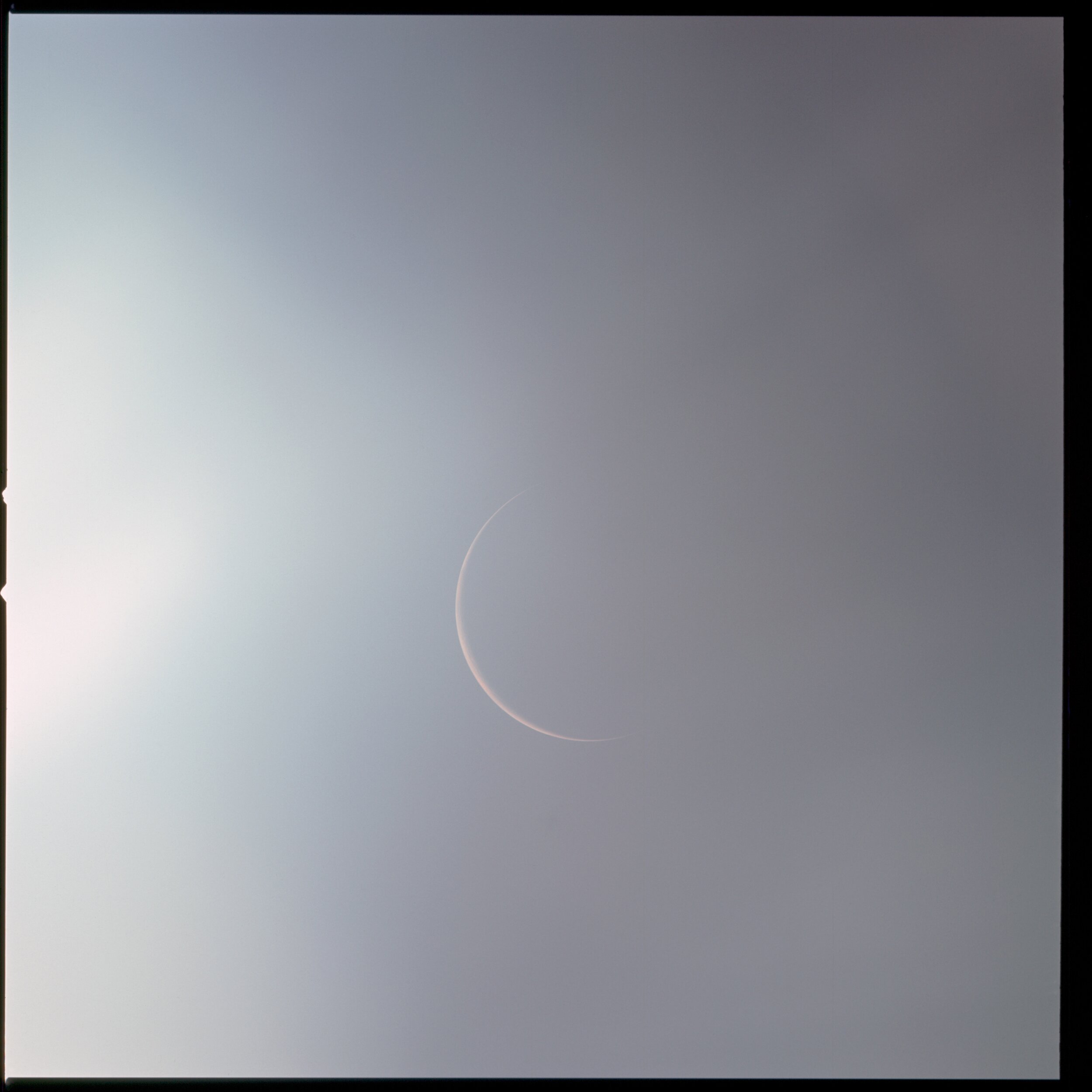

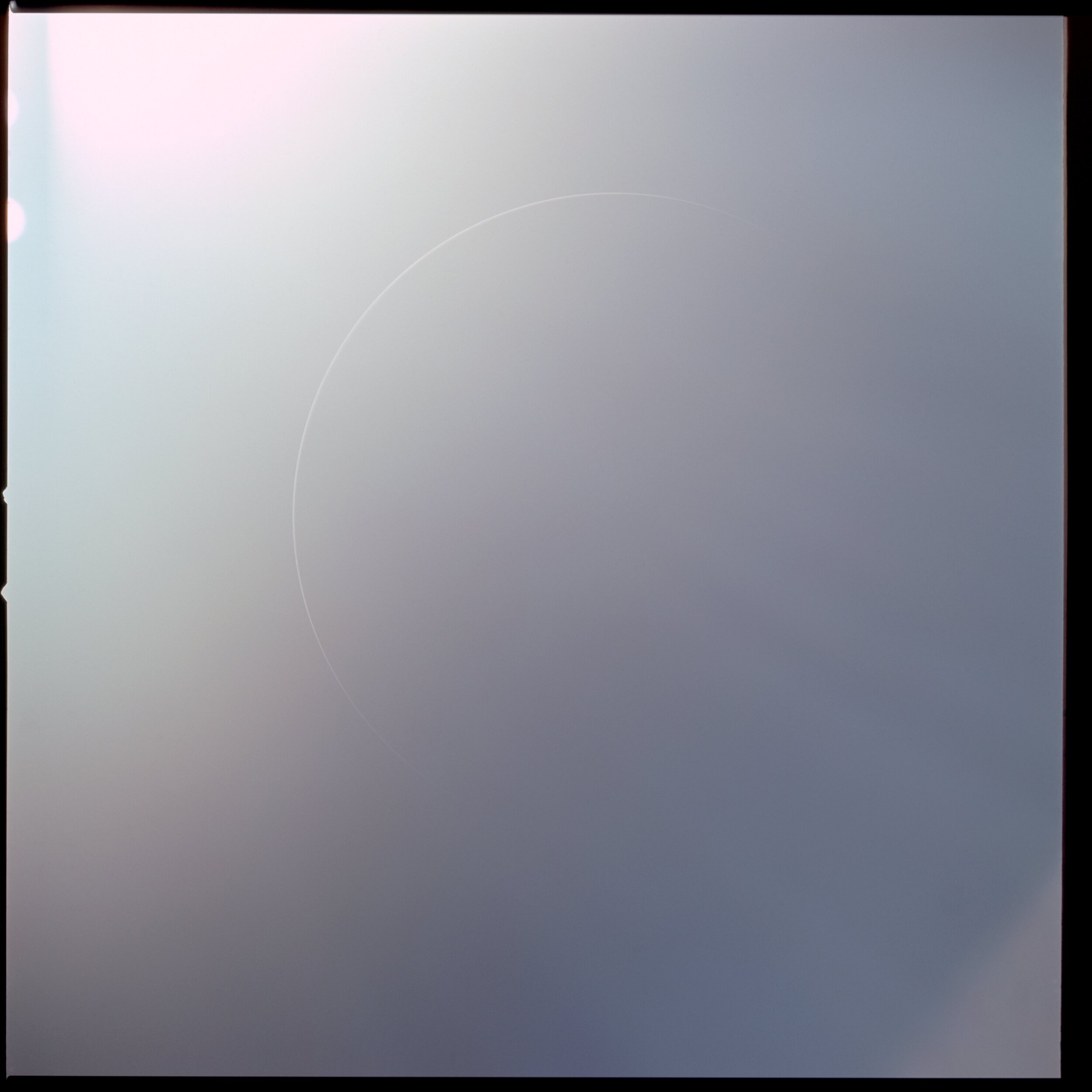

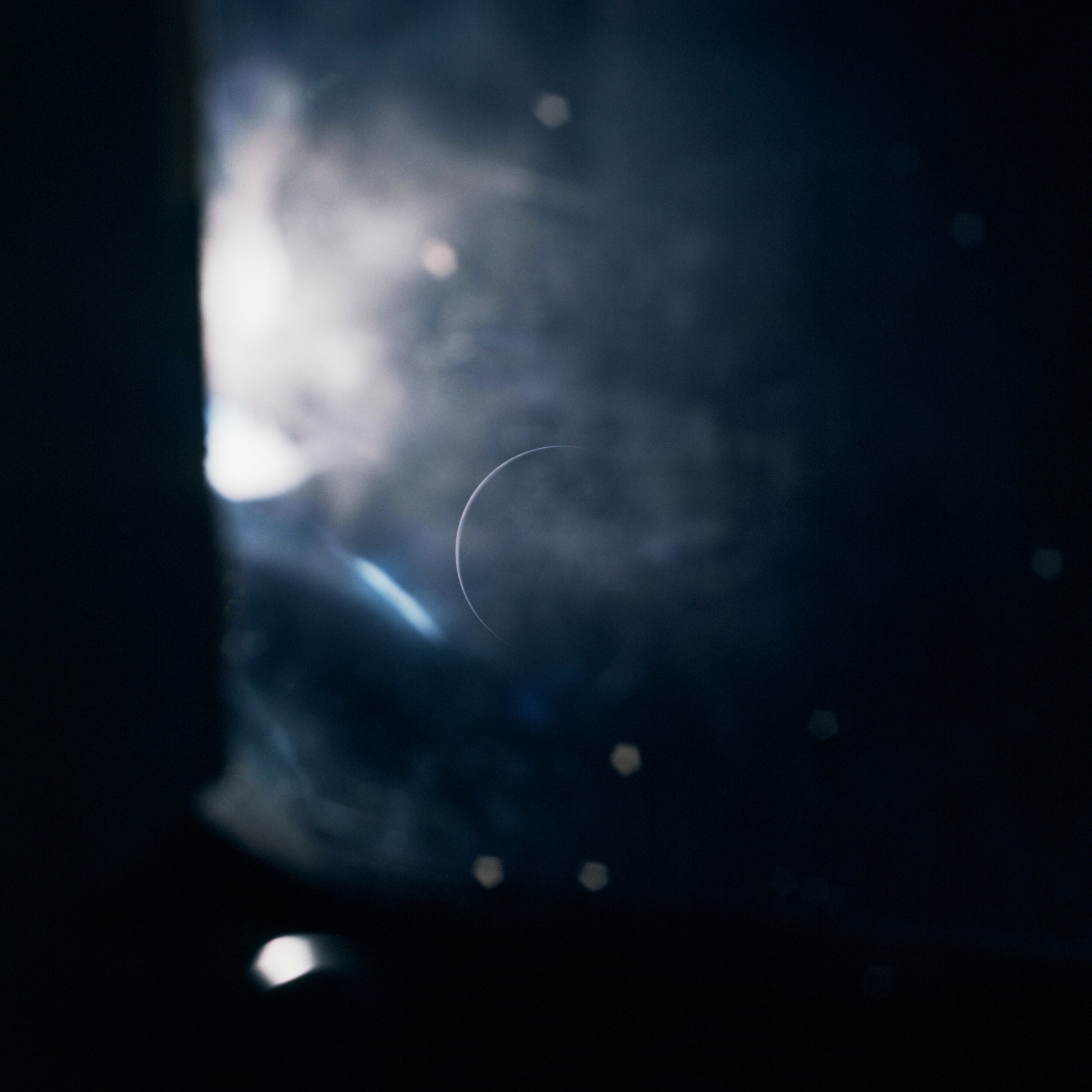

Unprocessed scan from JSC

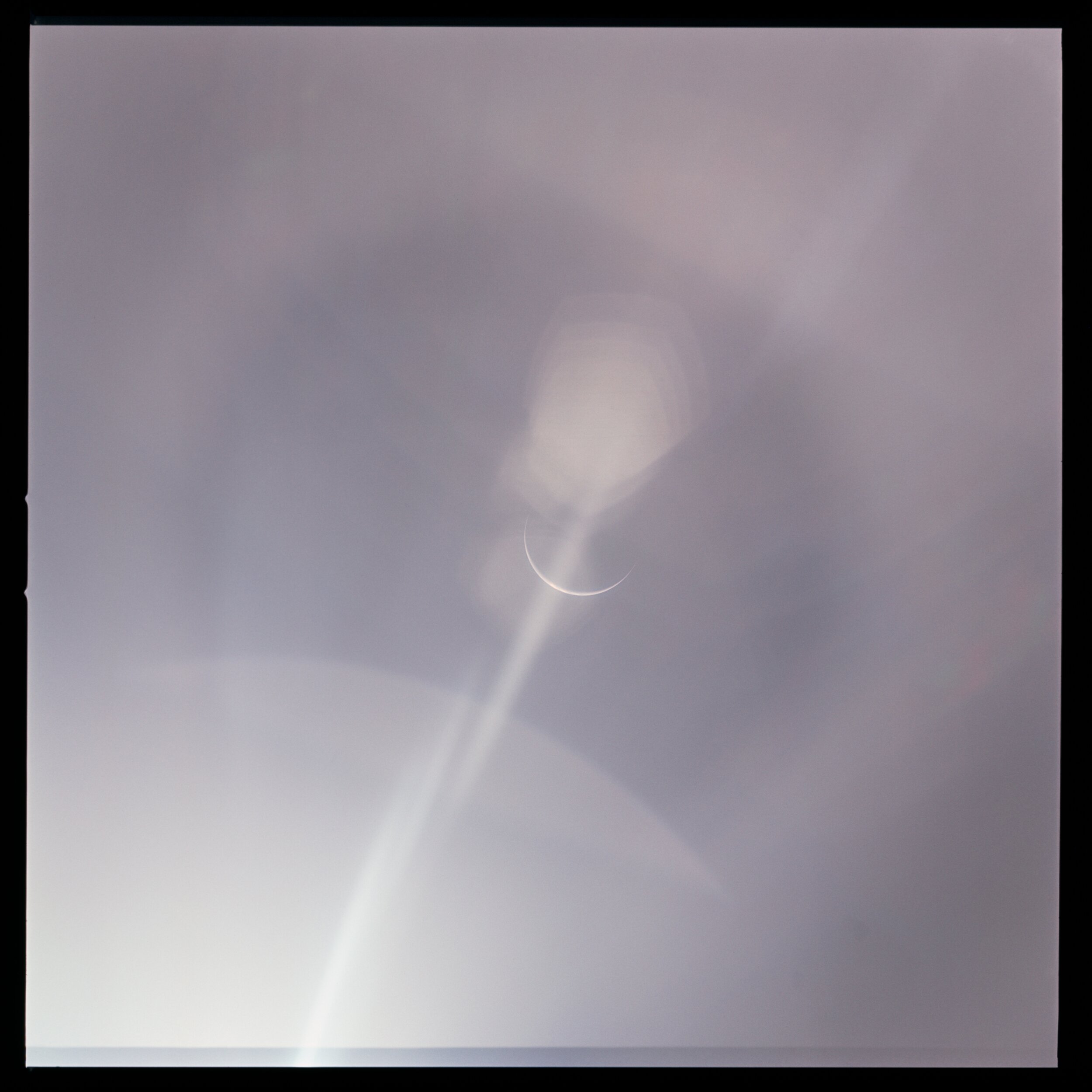

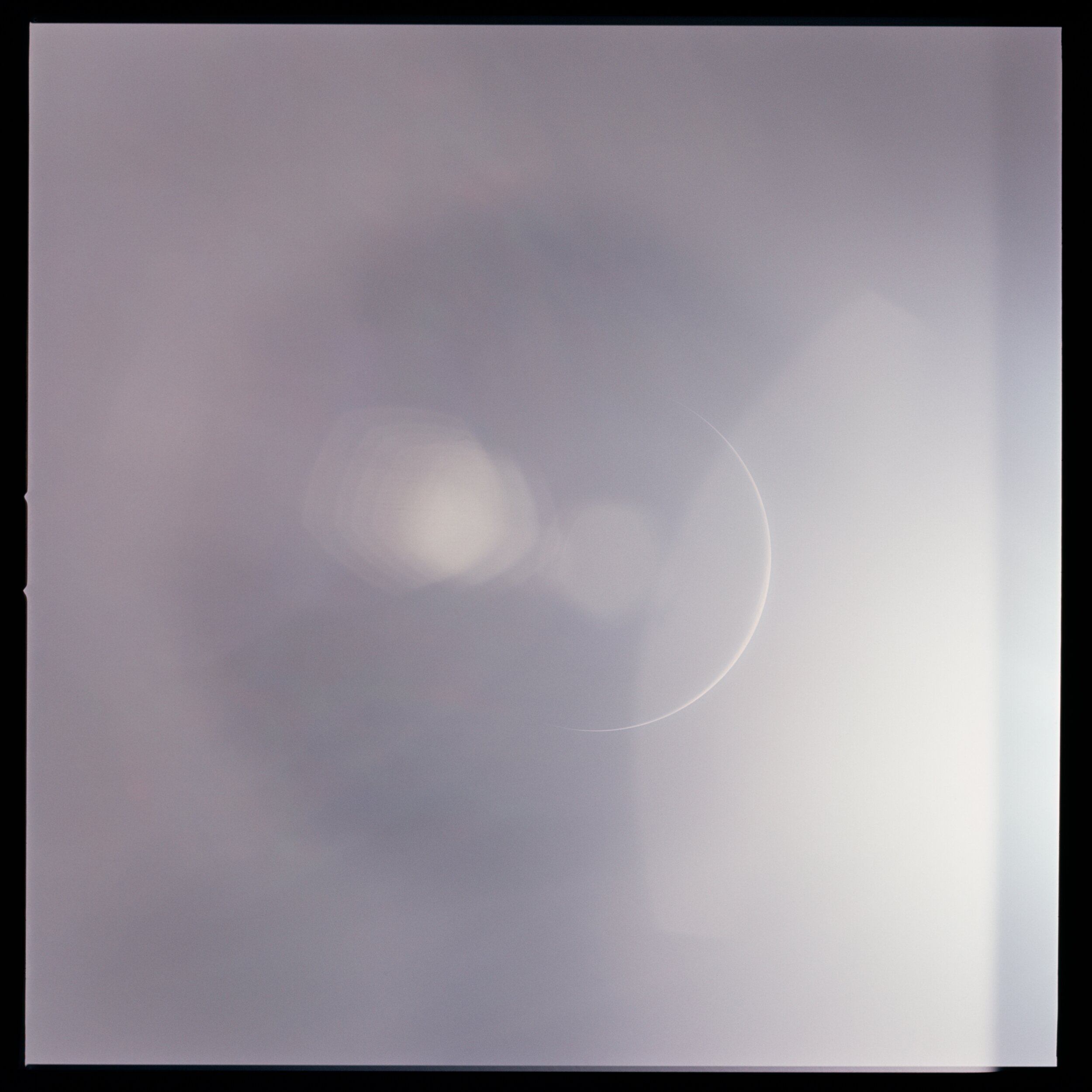

At first glance, they were beset by even more flaws than the reproductions: with dust and scratches; strange colour casts; extreme under- or over-exposure. But they held within them the potential to remedy these flaws and reveal their beauty. Filled with hope, I downloaded a scan of The Blue Marble, and tried my hand at restoration. To my lasting surprise, the preliminary adjustments for levels and white balance saw it come to life — already surpassing the reproduction used on Wikipedia.

Unprocessed scan from LPI

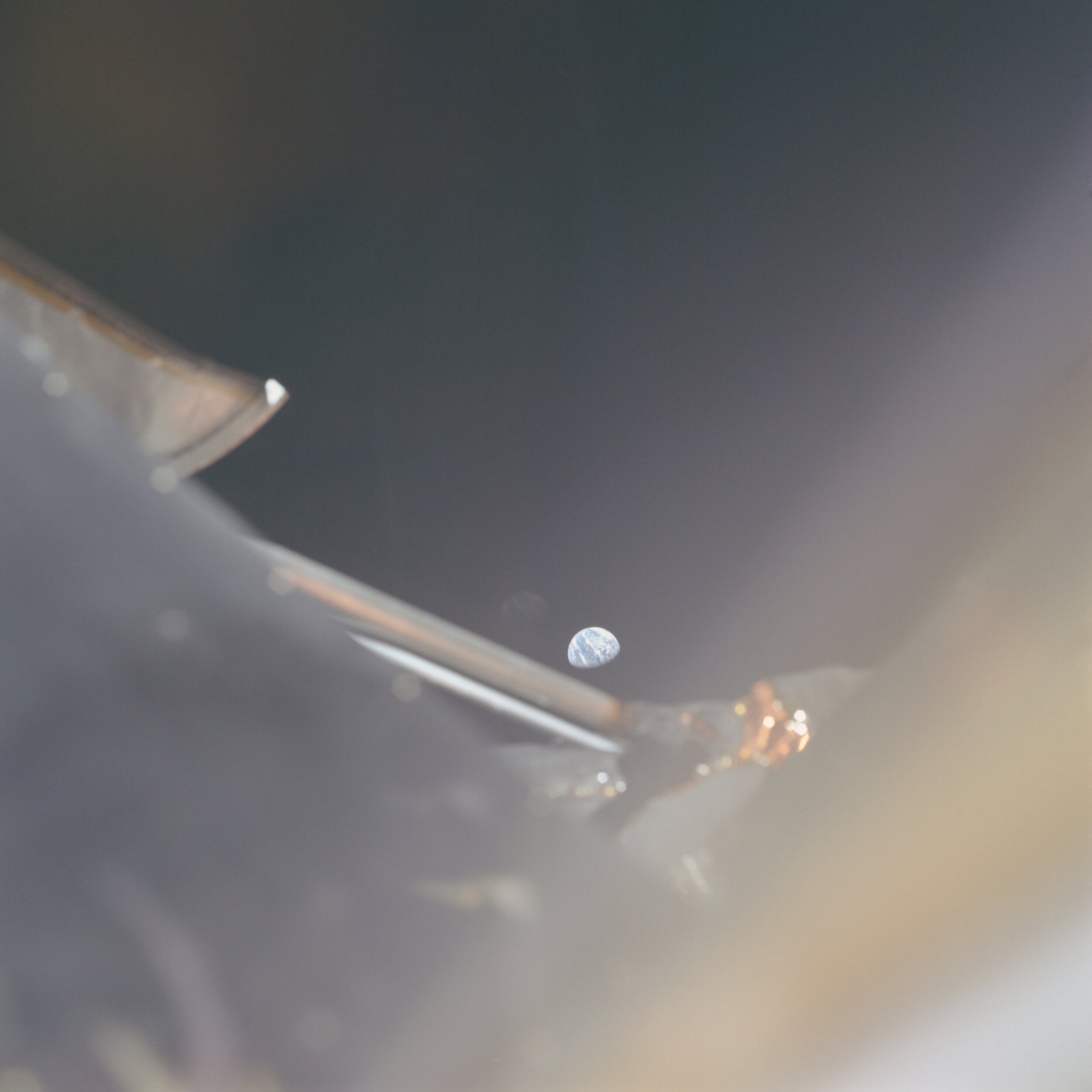

Intrigued by the possibilities, I began seeking out more and more images of the Earth from space. My quest eventually led me through more than 18,000 images from the Apollo program (every Hasselblad shot), finding every good photograph of the whole Earth.

These included many familiar images of our world, used in everything from environmental campaigns to background mattes for space films. But I also discovered a great wealth of photographs that were rarely, or never, restored at all. In some cases, the Earth was shown in such a strange and unprecedented manner that the cataloguers had not even recognised that the photograph showed our planet. In other cases, the photographs were deemed to be of such low quality that most of the available sets of scans do not even include them. And yet among these unrecognised or discarded shots were some of the very best photographs of our Earth ever taken. I believe there is as much value in finding and curating these, returning their lost beauty, as in the restoration itself.

Restoration

Restoration: before & after.

I restored these images over the course of many long evenings. On warmer nights I’d open the window to the Moon and stars and the black of space. The work was often slow and painstaking. But it was also deeply uplifting: seeing the images come to life, and gazing for the first time at the beauty of some of the lost pictures of our world.

I was guided throughout by two principles:

be true to the photographs

be true to the Earth

The Apollo photographs are historic works of art. So in restoring them, I sought to bring out their own beauty. I refrained from recomposing the images by cropping, or trying to leave my own mark or interpretation. Perhaps in some cases this would make a more pleasing image, but it was not my aim.

And the Apollo photographs are also a scientific record of what our Earth looks like. In particular, what it would have looked like from the perspective of the astronaut taking the shot. So rather than pumping the saturation or adjusting the colours to what we think the Earth looks like, I wanted to allow us to learn from these photographs something about how it actually appears.

The main changes I made were:

manually removing dust and scratches

manually removing the black crosshairs from the two images containing them

adjusting the black point until the background of space appears truly black

adjusting the contrast curve to bring out detail in the highlights and shadows

setting the white balance from the clouds or ice

What does the Earth look like?

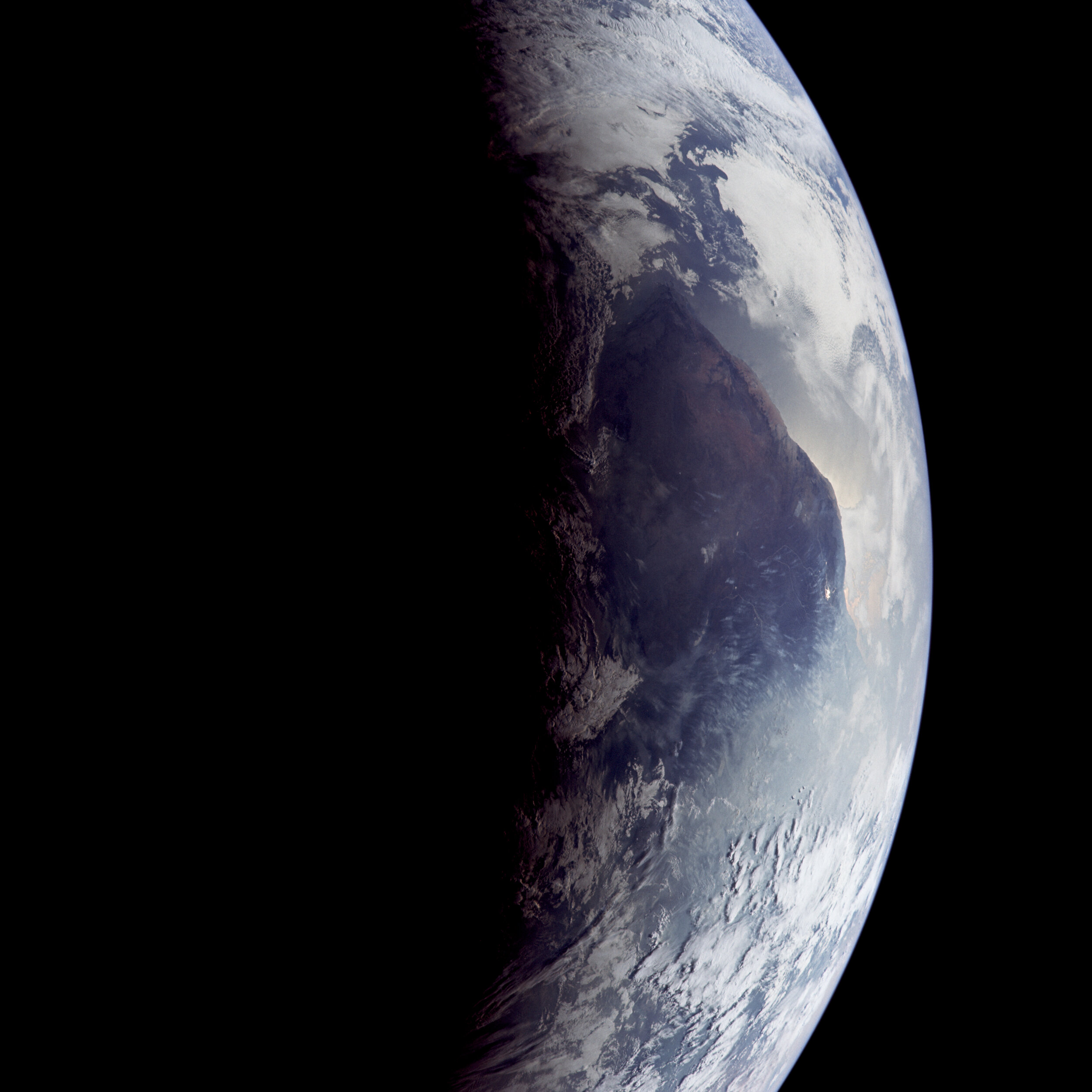

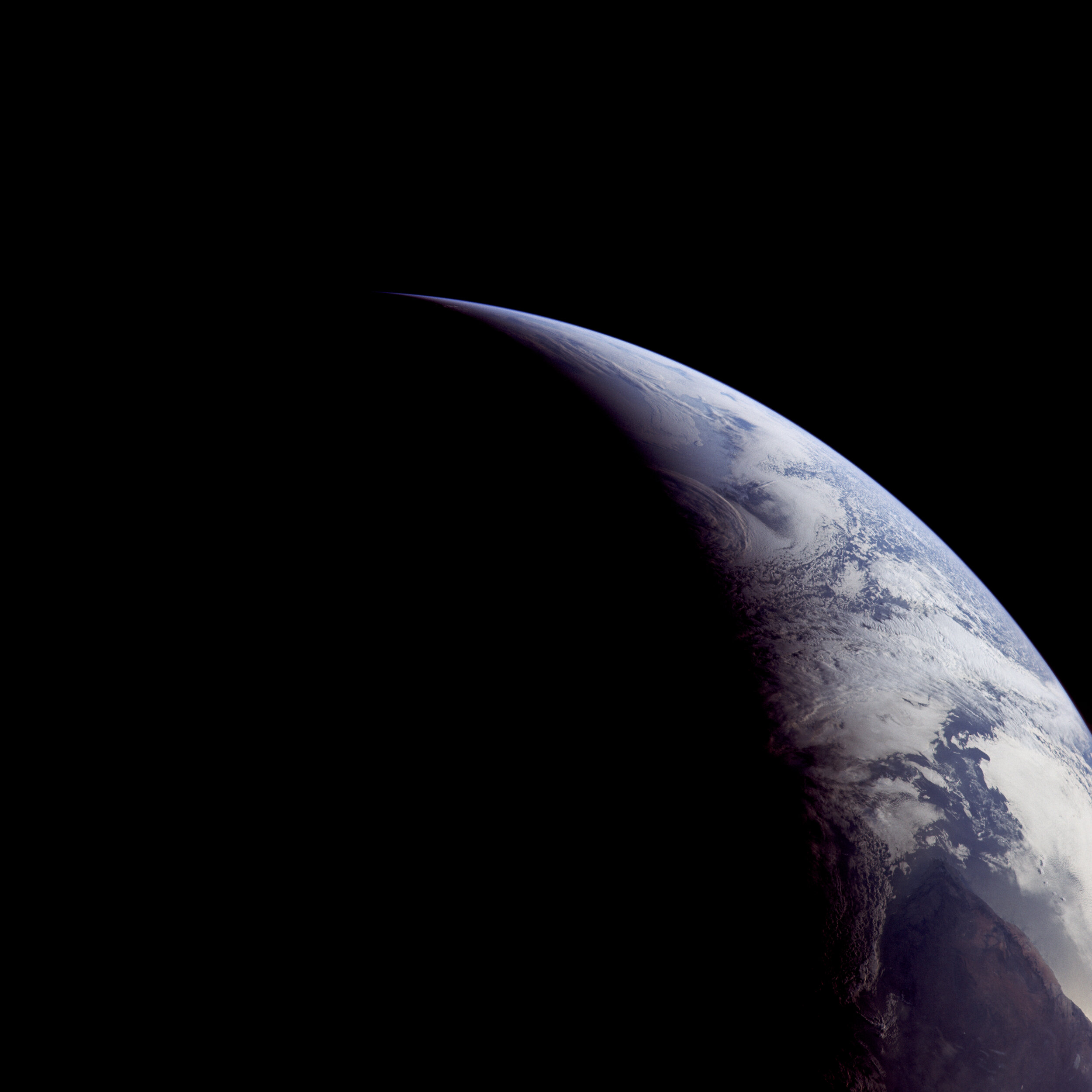

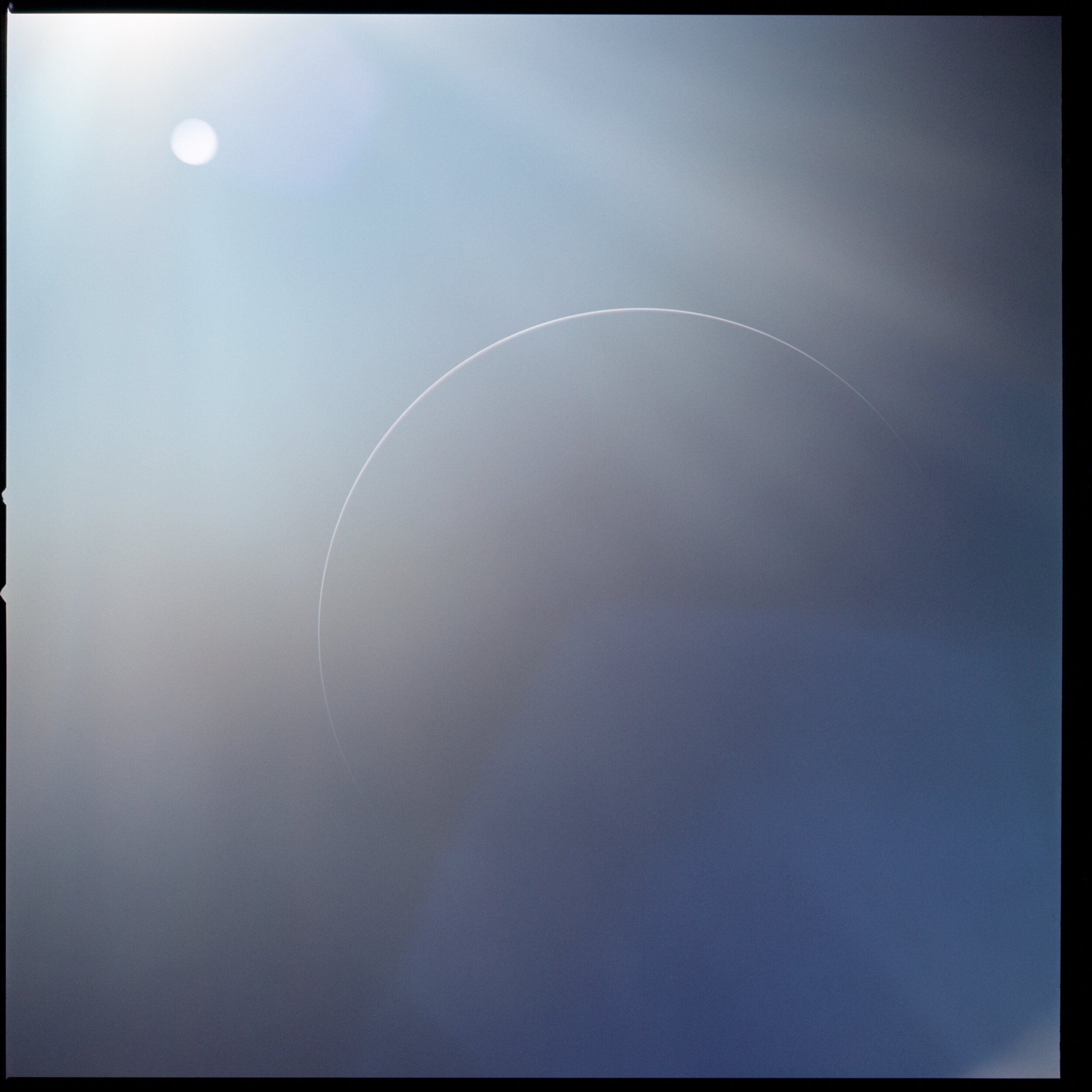

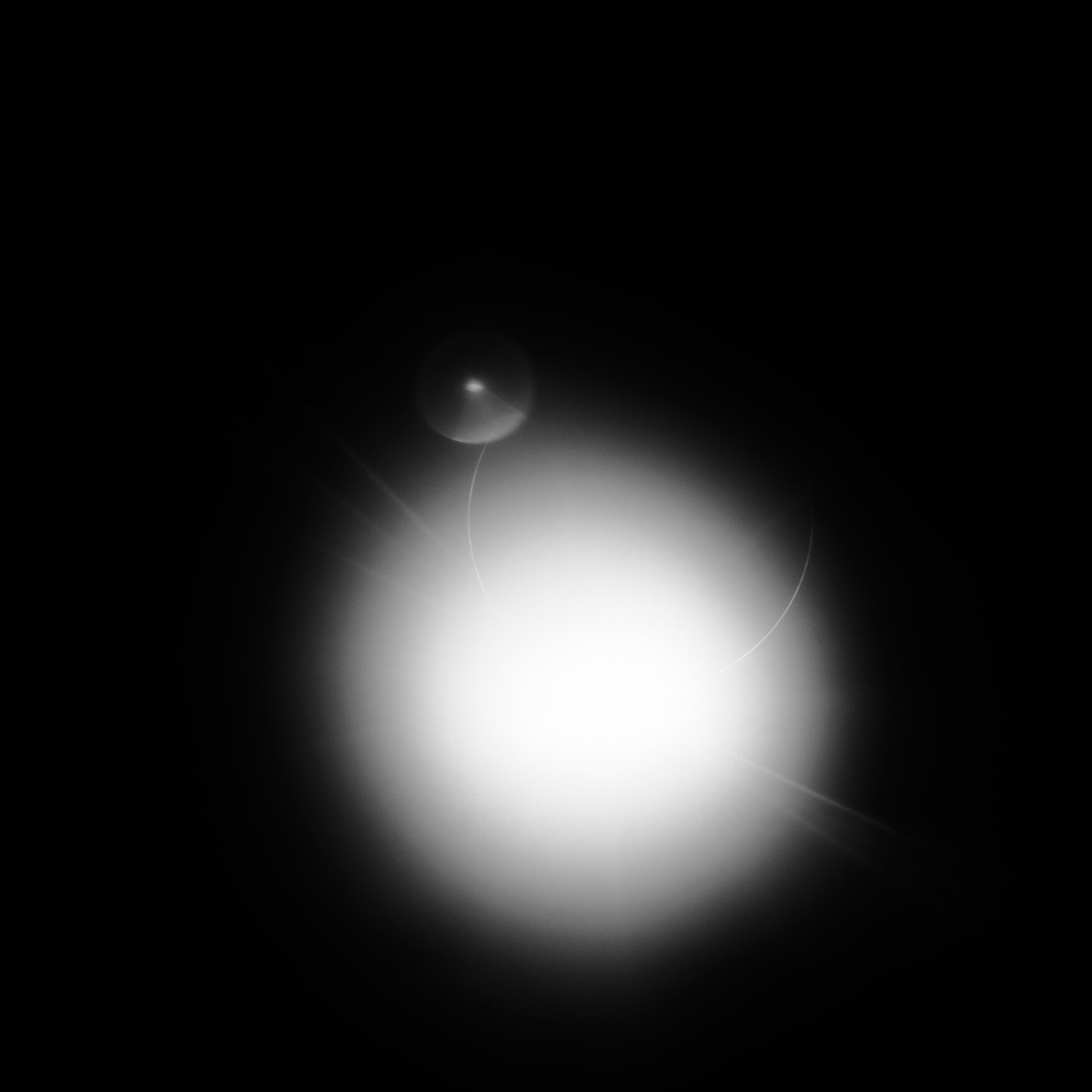

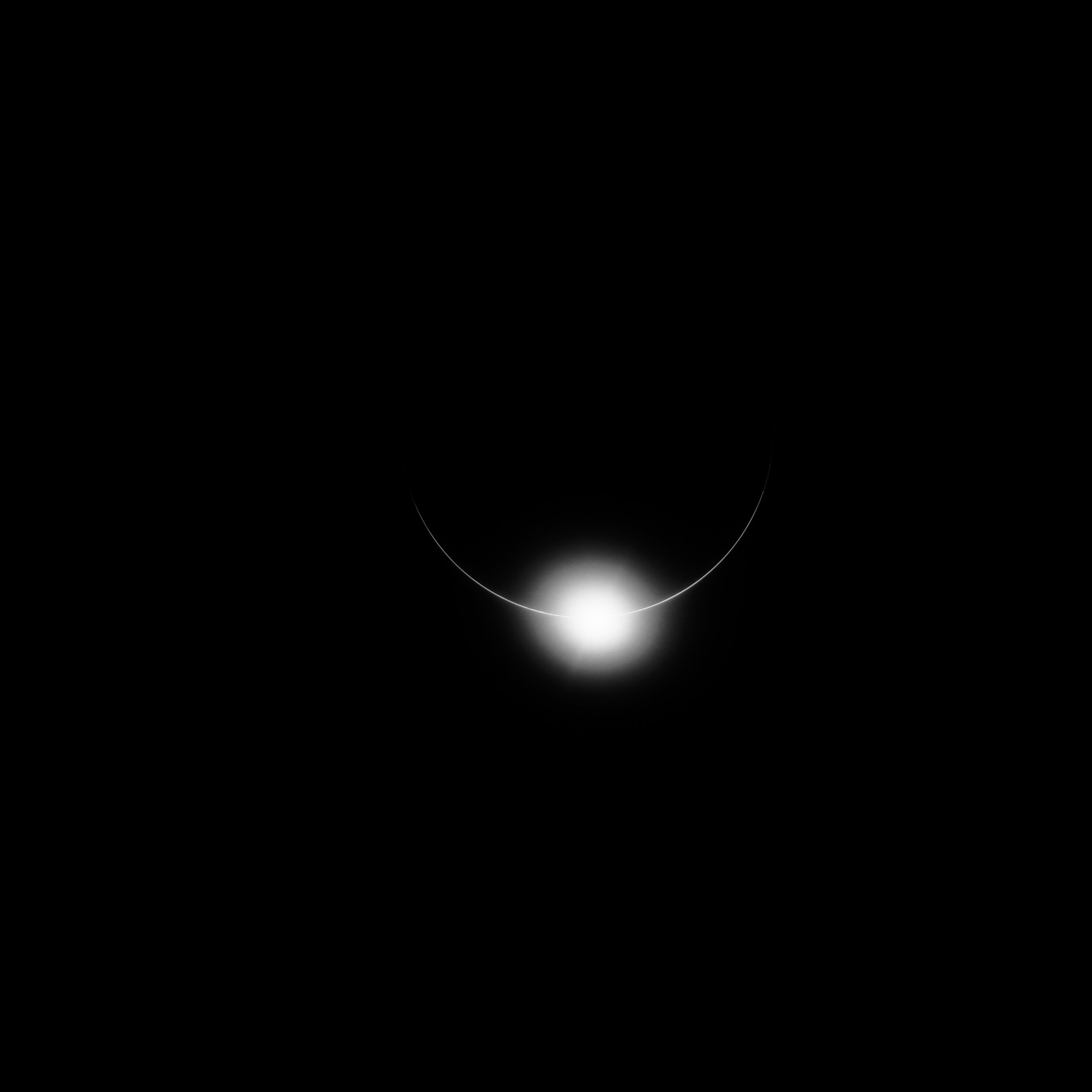

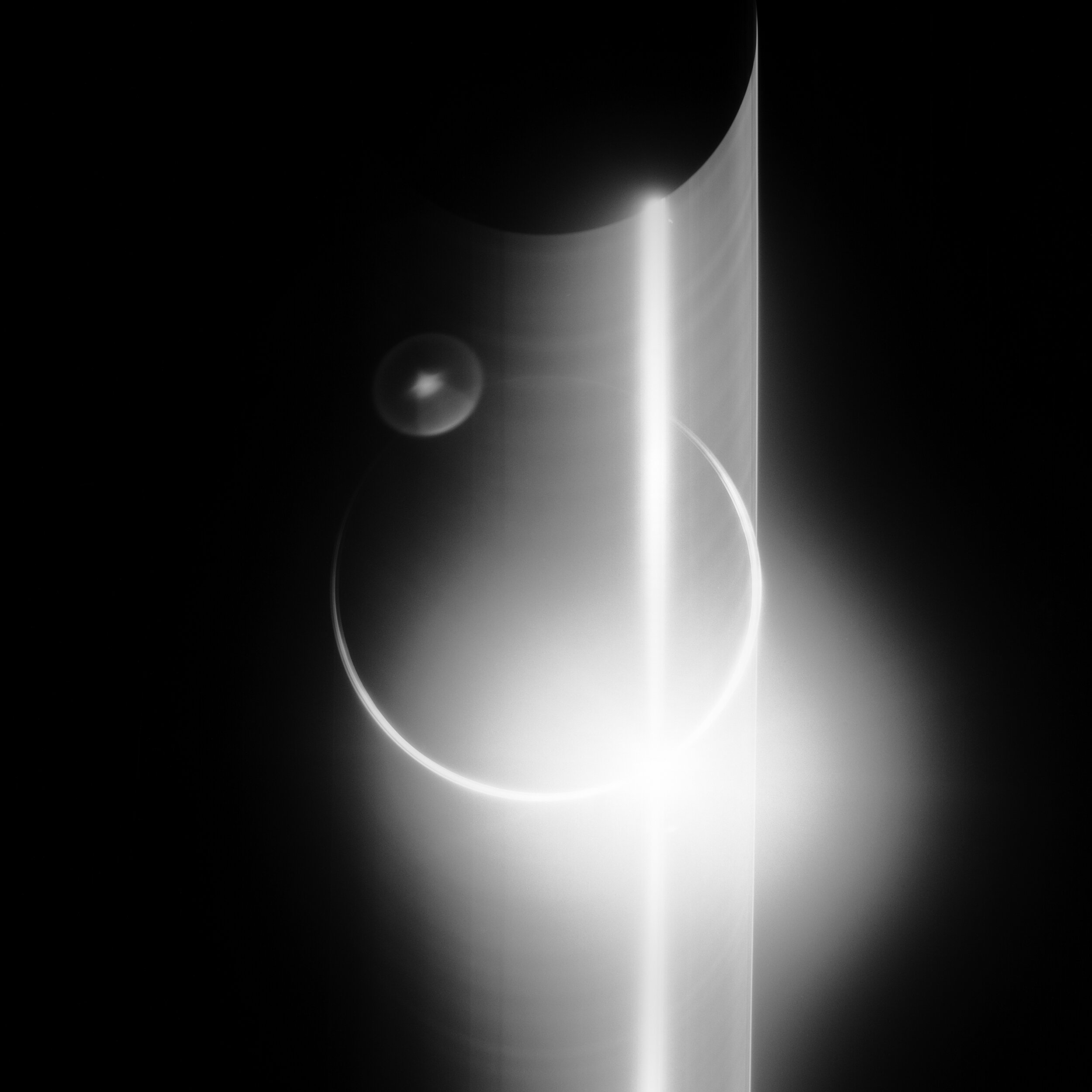

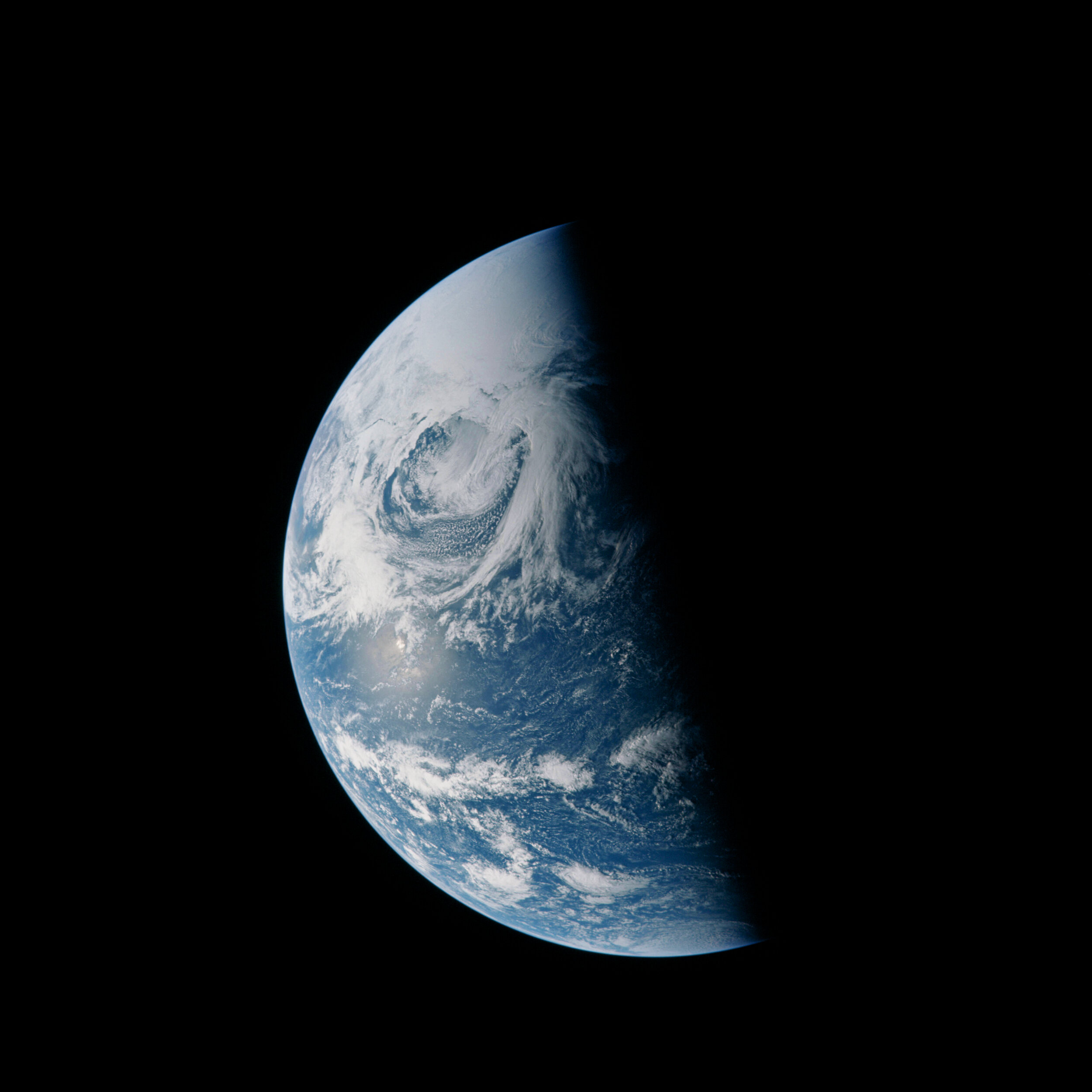

The Earth is almost invariably depicted as a blue and green circle. This bright blue disc with swirling green continents has become a modern icon for our world. But we can see from these photographs that the Earth does not much resemble its icon.

First, it is not green. Earth is mostly blue with ocean and white with cloud and ice. Then there are the brown tones of the land. In the most fertile areas, the land could be imagined as green, though it really appears as a dark olive or teal. The vivid green colour of foliage is lost in the atmosphere, just as tree-covered hills appear blue in the distance. And while it is hard to be sure, it seems that the colours of the Earth are less vivid than typically depicted, and instead have an almost pastel quality.

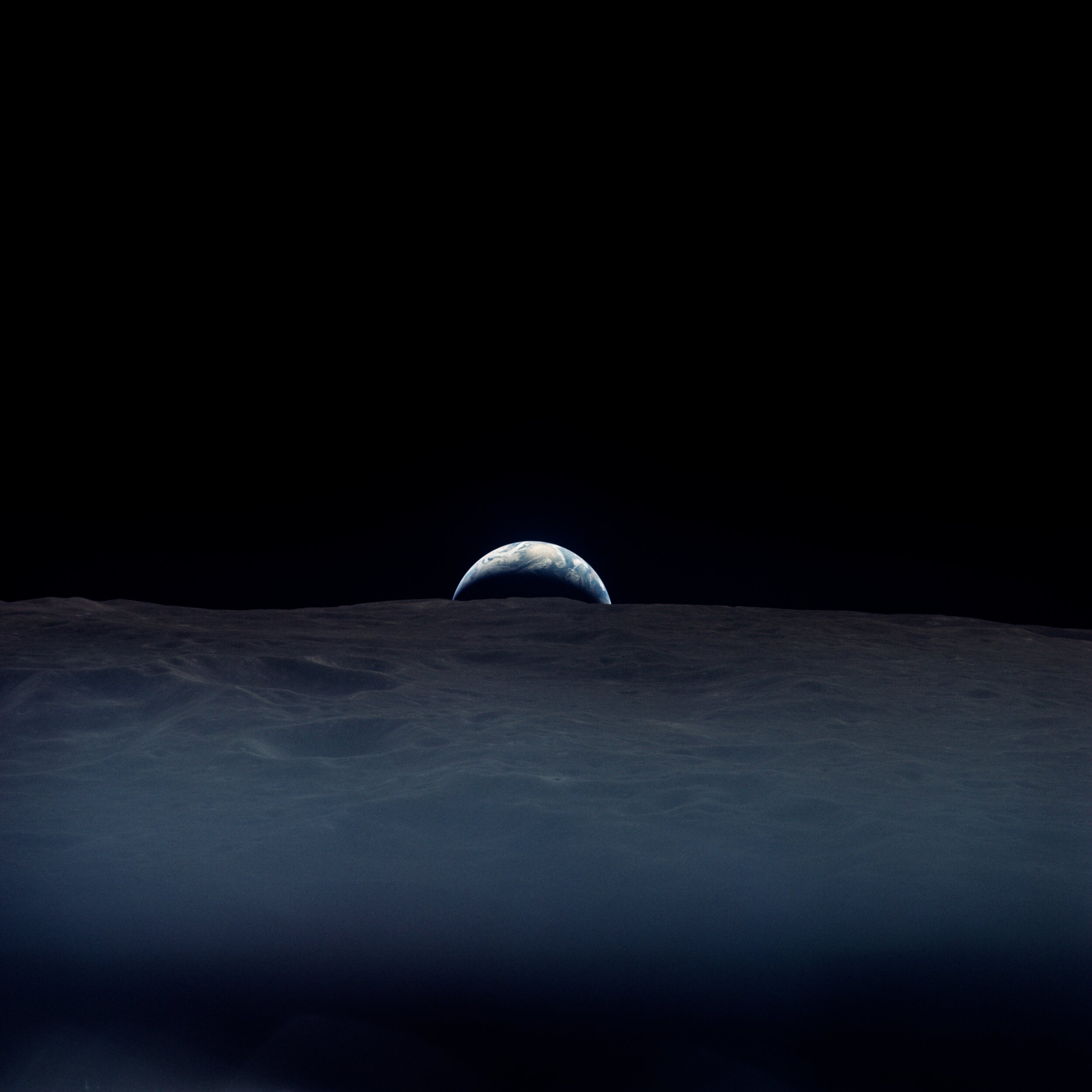

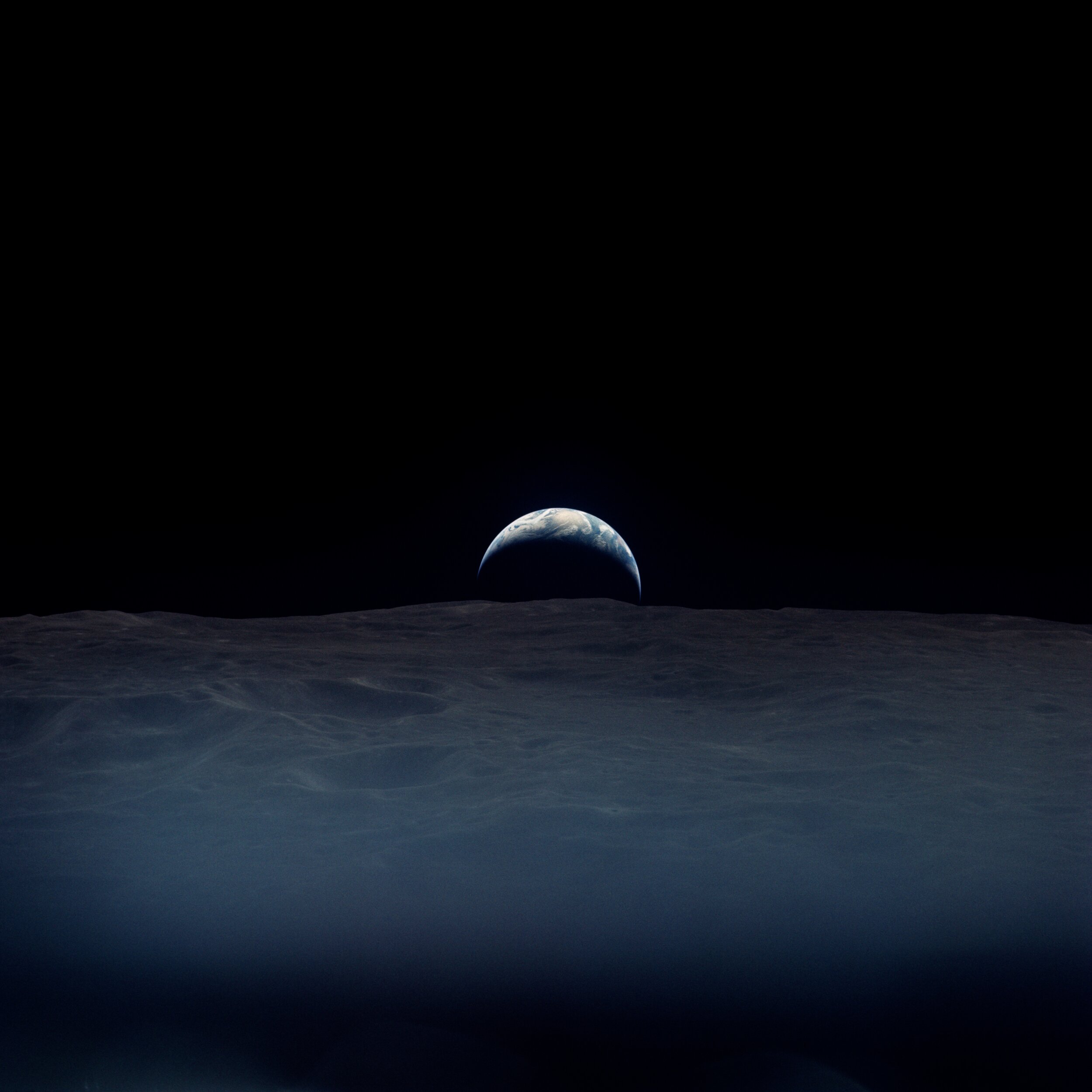

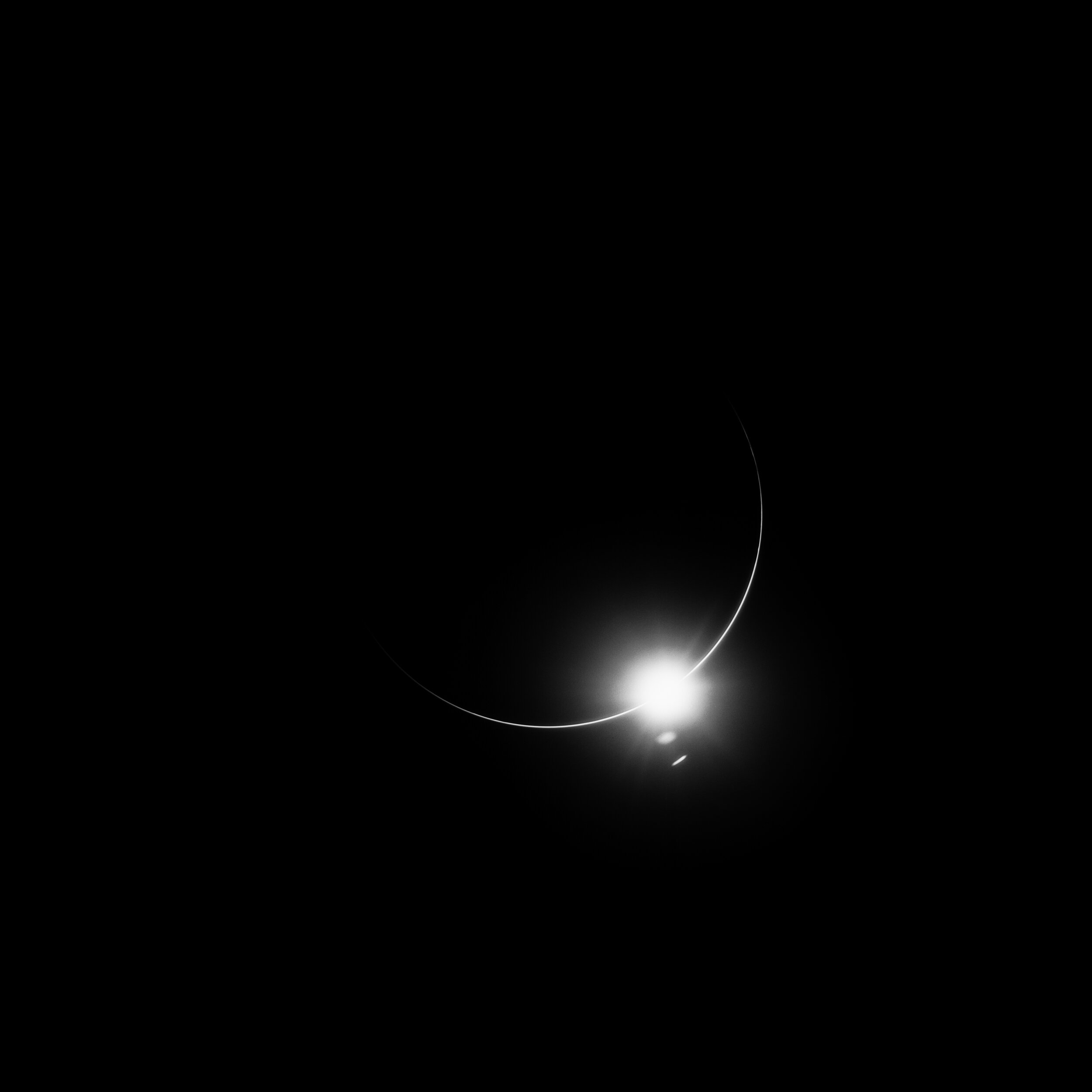

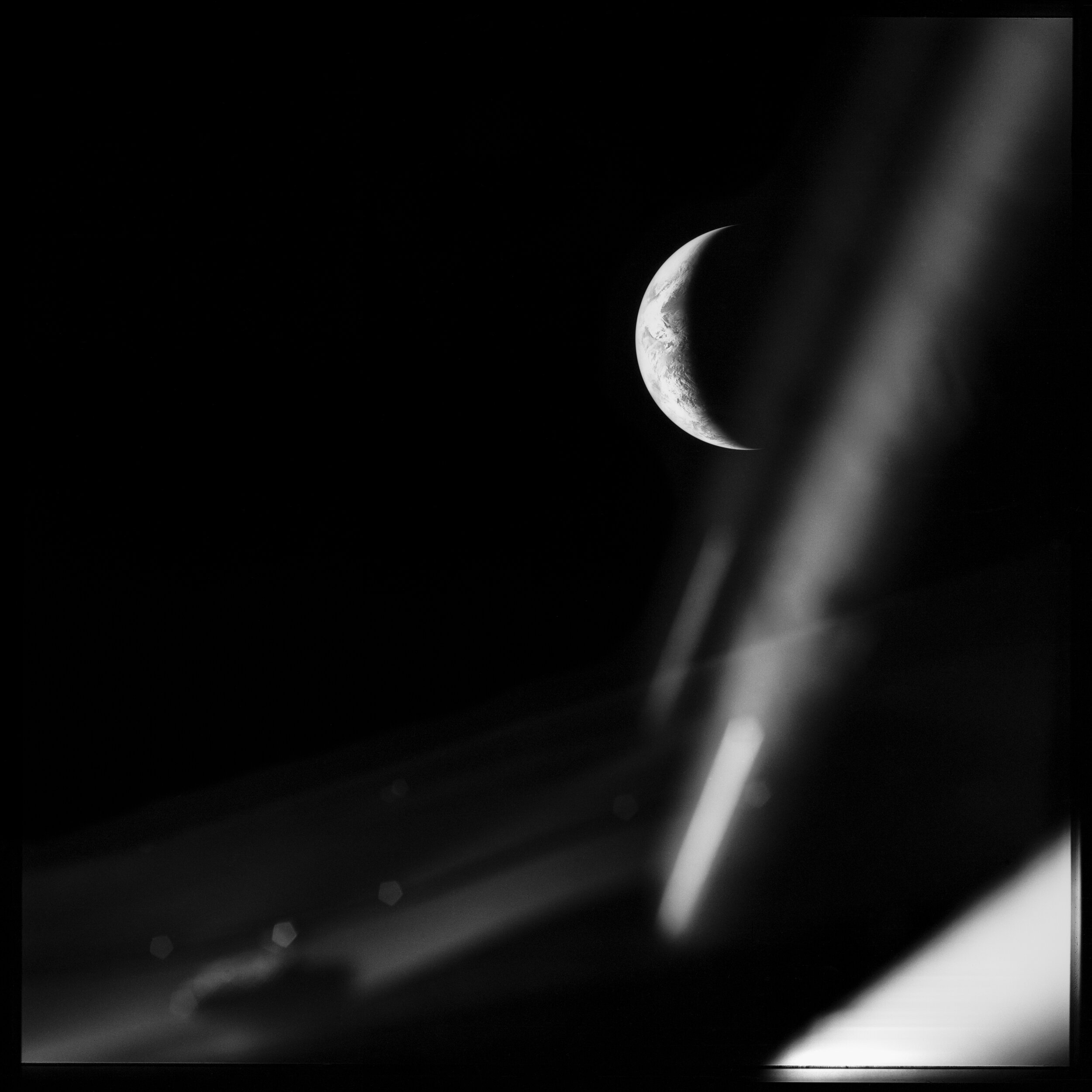

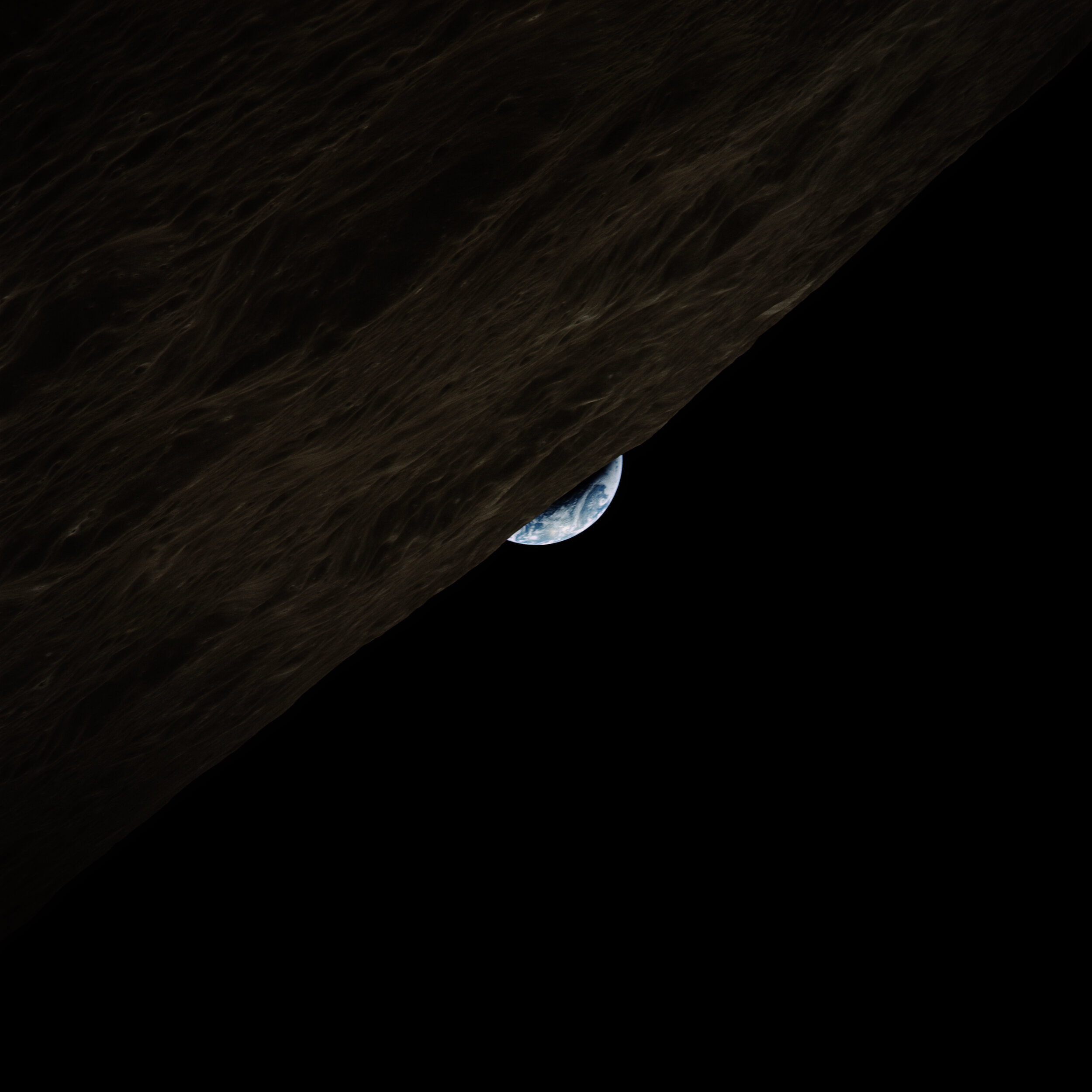

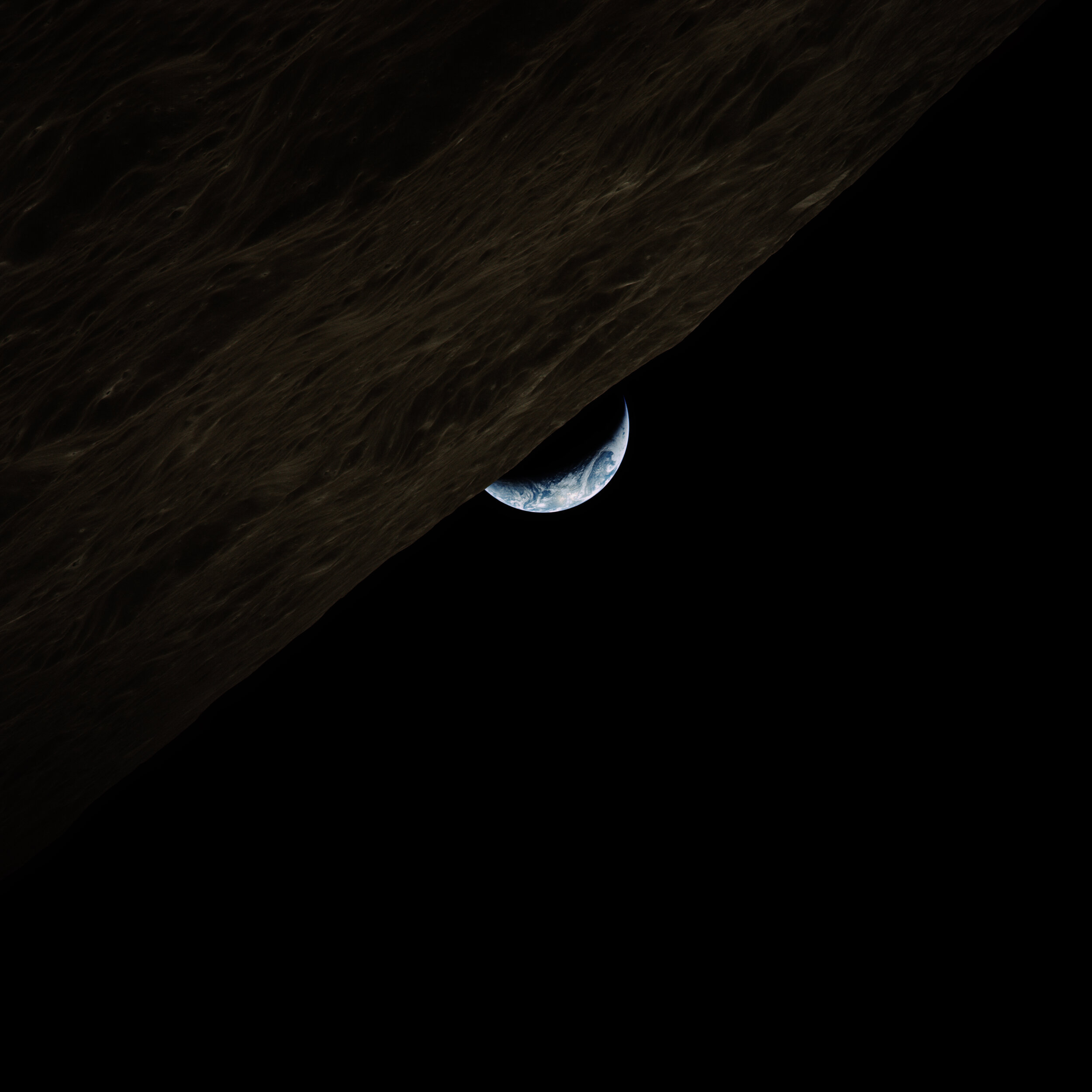

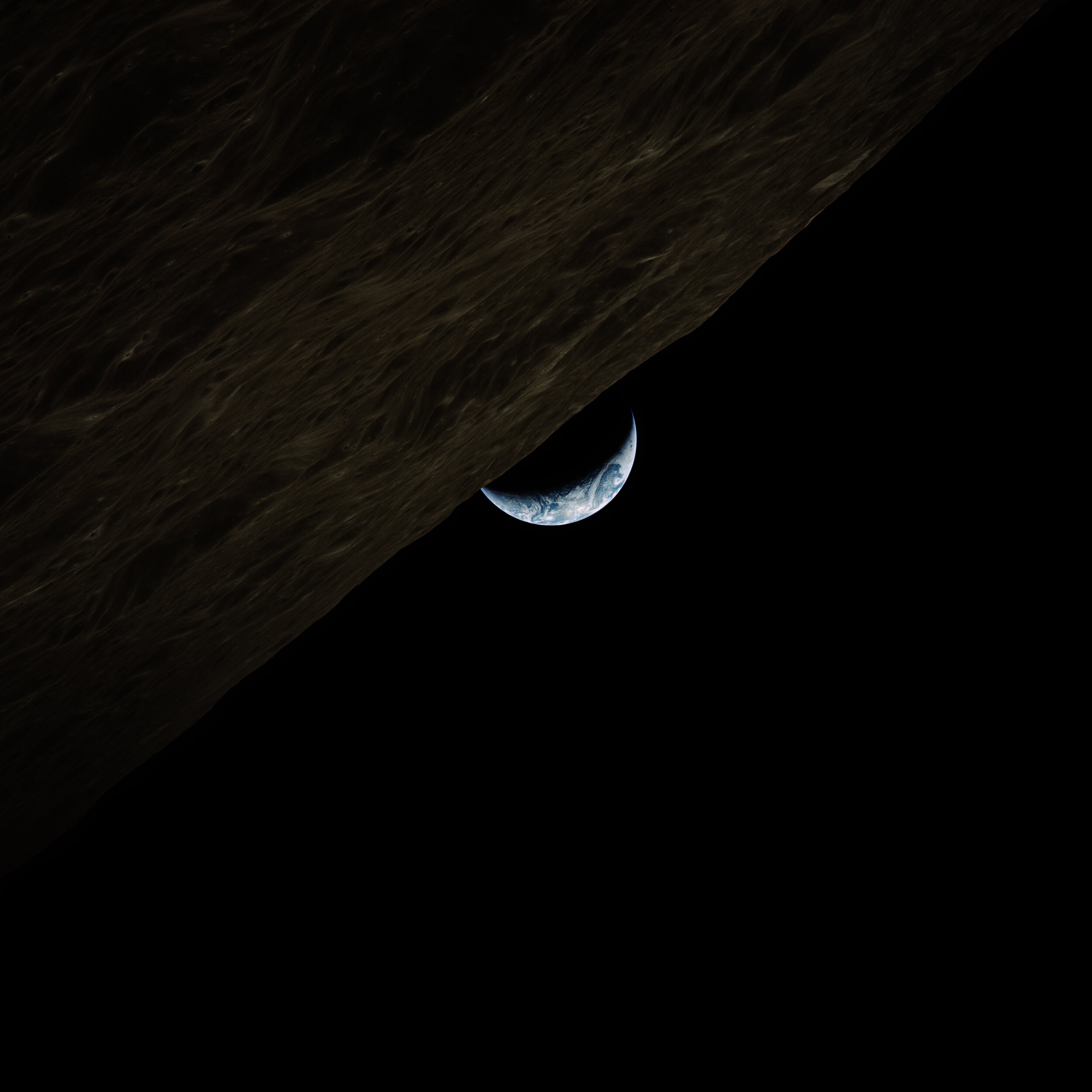

Second, and more subtly, the Earth almost never appears as a circle. Exactly like the Moon, it would almost always appear in gibbous or crescent phases. And like the Moon, the part that is lit by the sun so overwhelms the faint light from the part that is not, that the latter appears almost pitch black.

We sometimes do see the Earth depicted as gibbous, but almost never as a crescent. Indeed that particular crescent shape is such a potent icon for our moon, that in many pictures of a crescent Earth it takes a substantial effort not to read it as the Moon. And the images of the impossibly slender crescents are nothing like our mental image of our world.

Yet for all that, there is a deep beauty in how the Earth actually appears. The blue globe, wreathed in white, is serene; majestic. And the crescent Earth takes one’s breath away. It’s time to improve our mental images; to update our icons.

The Future

While I’m very pleased with how these restorations turned out, they are not the last word; not the definitive images.

First, they are only a selection from the vast vaults of Apollo. I’ve had to leave out many great photographs, which others may choose to restore.

And newer, better, scans of the Apollo photographs keep coming out. This will allow reproductions that are even crisper, or that bring out more detail in the highlights or the shadows.

There are also many people who could do a better job of the restoration. I’m a passionate amateur and was proud to be able to play a part, but there are professionals whose technical skills and judgment far surpass my own.

And there are a range of different choices that could be made, drawing out different aspects of the photographs. This is especially true if people make more radical transformations (such as intense contrast, cropping, or saturation) that I’ve refrained from here.

Finally, and most importantly, new photographs will be taken. Since I began this project, a new mission to the Moon has been confirmed, planned for 2024. The photography of the Artemis program should rival — or even surpass — that of the Apollo program. I can’t wait.

Book

I restored these images over many long evenings. During the days I worked on a book, which would consume me for three years. I am a philosopher at Oxford’s Future of Humanity Institute, and this book was about humanity at the largest scale: the ten thousand generations who came before us, the millions of generations who may follow, and how that entire future is at stake. For with the development of nuclear weapons, we have entered a precarious time where humanity has gained the power to end our story before acquiring the wisdom to ensure we don’t.

So I was thrilled that the first use of any of these restored images was for the (North American) cover of The Precipice. All the more so, that it is one of my favourite shots: a hauntingly delicate earthrise, captured by the crew of Apollo 12, speaking both our fragility and our potential.

Credits

These restored images may be used freely for non-commercial purposes, so long as they are credited to NASA (in a way that doesn’t imply NASA’s endorsement). For more details, including for commercial use, see their media usage guidelines.

There is no need to credit me if you use these restorations. But if you choose to, my name is Toby Ord and this page is tobyord.com/earth

For my own part, I’d like to thank:

David Bigwood from LPI for personally sharing some of the very latest and highest quality scans by JSC and LPI.

Clouds Across the Moon for determining the times, dates, and visible places for each of these historic photos.

NASA, JSC, LPI, ASU, and Project Apollo Archive for all their work in preserving, scanning, and distributing the originals.

The 24 astronauts who travelled so far from home and showed us our world.

You can find the source of each image in the slideshow captions, with the link to the unprocessed scan, where available. The scans are courtesy of:

A set of recent LPI scans that aren’t yet online

There are also a number of art books with excellent restorations of Apollo photographs (though many are now out of print). I recommend Apollo: through the eyes of the astronauts by Robert Jacobs (et al), Apollo VII-XVII by Floris Heyne (et al), and my favourite: Full Moon by Michael Light.